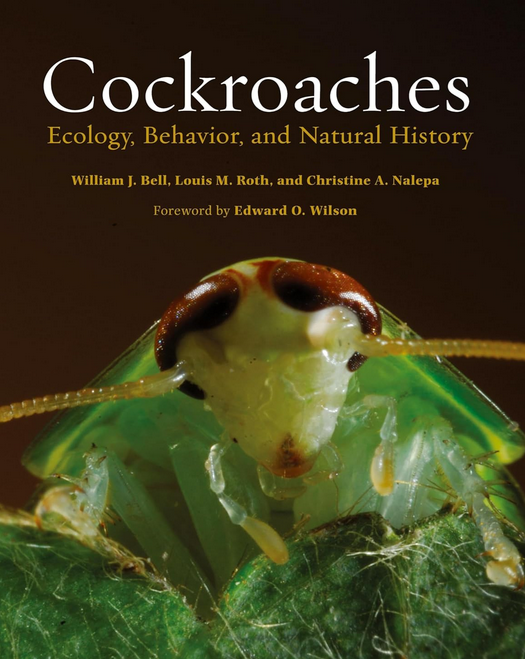

I went back to trying out a text book because there were surprisingly few books on cockroaches. In fact, something I learned from this book is that there is surprisingly little research on cockroaches. A numerous and diverse group of insects, most research seems to be on the pest varieties and how to kill them.

This book by the late William J. Bell and Louis M. Roth and continued by Christine A. Nalepa isn’t as long as what you might expect regarding such interesting insects, but it is thorough. It’s even funny. Though the number of jokes decreased as number on the pages increased, I did have some laughs, and they helped get me hooked. What I found most fascinating was that after so much study of ants, cockroaches surprised me thoroughly by being the group that produced termites. They do the entire colony thing very differently from ants, having kings and queens together. Termites were basically small cockroach families that found security and food digging into wood and found ways to expand. I won’t ruin it all, but they basically took normal features of cockroaches and adapted either in behavior or in physiology in rather simple ways. Once you understand them, you’ll be surprised anyone could think termites aren’t cockroaches!

Other interesting aspects of cockroaches include mating where males often provide a sweet snack on their backs to entice females to come close. They don’t always mate, but it does help. And after they mate, the females of some species give birth to live baby roaches! They may even carry these babies around on their bodies. Female cockroaches can be wonderful mothers. Just don’t call your mom a roach and tell her it’s a compliment.

In conclusion, it’s a text book. Not lengthy, but still a text book, so you have to be prepared for that. The narrative books of Heinrich or Ackerman have advantages in readability, but a systematic approach is also an advantage. I still kill any cockroaches in my home, but I am fascinated by them more.

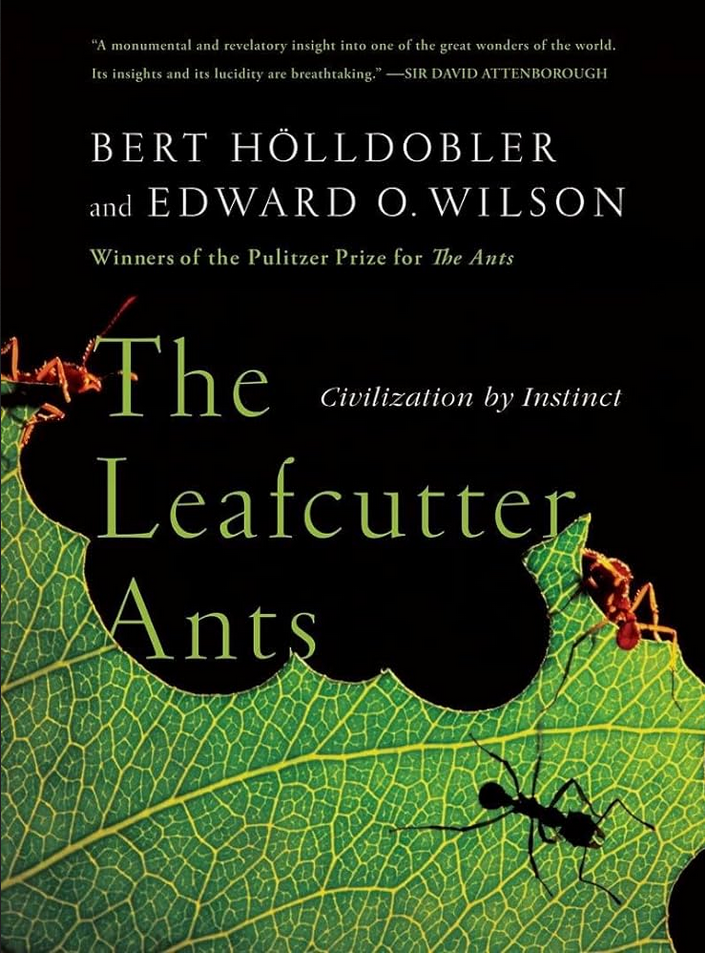

This book, written by Bert Holldobler and Edward O. Wilson, the same men who wrote The Ants, is an improvement in many ways. Some of this is due to technology. The Ants simply lacked as many great photos as The Leafcutter Ants, but 20 years of progress in photography is a lot. There likely was also more information about leafcutter ants available due to more research having been done and published during those years. But mostly the improvement is that this book, while still very technical and dry at times, was much more readable and much more digestible than the massive book about all ants. There was a large section about leafcutter ants in The Ants, but this really went into depth in ways the other had not.

Leafcutter ants have some of the largest colonies, extending well into the millions and excavating large areas of soil underground. They typically harvest leaves from trees or grass, depending on the species, chew up the leaves into small chunks, fertilize them with feces, and then grow a specific fungus inside their nests.Every ant colony is surprisingly complex; more complex than you would consider, but leafcutter ants might be the most complex, and that is probably why the authors chose to write a book only about them.

Some of the most interesting information I learned was about how the mutualistic fungus grown by the ants seems to communicate with them in some unknown (at least at the time of publication) methods. For example, plant material laced with toxins first gets collected by the ants, but after several hours, they reject it. They reject it so wholly that they won’t collect the same type of plant material even if it isn’t laced and they continue to reject it for many weeks. Another really cool feature is that the ants even have special structures in their bodies designed to house bacteria that produce chemicals that suppress the growth of fungi harmful to the type of fungi they grow. Probably my favorite bit of information relates to how ants often stridulate (make rhythmic vibrating sounds), and leafcutters apparently adapted this behavior to help them cut leaves. It seems vibrating rapidly helps them cut leaves like a saw. It is pretty wild how involved and complicated the ants’ behaviors and physiology are to the growing of fungi and I only gave three of my favorite ways.

My biggest complaint about this book was that the authors really stuck to their guns when it came to focusing on leafcutter ants. There are many species of leafcutters covered, but the Holldobler and Wilson revealed tantalizing information about closely related species that grow fungus on detritus, or that grow yeast instead of fungus. I thought a couple more pages on those cousins would really help me better understand the evolution to–and potentially away from–leaf cutting.

In conclusion, this book has great balance of being in-depth, technical, and readable, making it a very digestible way of learning a lot about this relatively small group of ants. I learned a lot, recalled more, and enjoyed the experience.

Edward O. Wilson, one of the authors of The Ants reviewed earlier, was an accomplished author as well as researcher. I started this book many years ago and had to put it down for other research, but finally got back to it. The book is, as clearly titled, about the diversity of life–how it appears, how it disappears, and what we can do about it.

In the past, I have mentioned that I don’t care much for poetic description, but this book changed my opinion on that. The opening chapter is so well-written, I was quite surprised it came from this author. After my experience reading The Ants, which I described as, “does not read well,” I expected something dryer than what I found. I thoroughly enjoyed this writing. Unfortunately it does not stay that way. Some chapters are still so technical in how they are written that the style could be jarring. The notes in the back state that some of the book came from different things he had already written, so he could have been in very different states of mind when they were written, not combining them as seemlessly in this book as he would have if they had been written all together.

One thing that I enjoyed learning was thinking about how niches are filled up. That, generally-speaking, the same ecological niches are filled in every habitat wherever they are (except for a few exceptions, especially on islands). One way the author described it was imagining South America before its connection to North America. He said that it would look much like wild areas of Africa look today, just that everything will look slightly off. Similar creatures filling the same niches would be in both places, but similar is not the same. While many would look very similar (imagine four-legged animals browsing grasslands), considering giant sloths as filling the same niche as African elephants is a really neat and eye-opening way to think about ecosystems. Different animals, similar results. Radical exceptions do exist, such as vampire finches found only in the Galapagos. But generally, with enough space and time time, species in novel habitats will specialize to consume food resources in a similar way as extant species elsewhere.

Much of the first half of this book was about evolution, and although I am fairly well-versed, there was still much to learn, even when at the margins. Learning from experts at the level of the two-time Pulitzer prize-winner and Harvard entomologist allows you to learn more thoroughly, because they know so many more topics and sub-topics that most would not realize to consider.

However, while the first half of the book is about, evolution, speciation, and ecological diversity, the second half is about extinction, warnings about the future, protective measures, and ethics. While I don’t really enjoy the preachyness (not that I blame anyone being preachy when talking about human-caused extinction) or find it helpful, I did still learn a lot, especially in the section on extinction, both natural and human-caused. First off, I appreciated that the author didn’t hold back for any group of people. We know the problems with industrialized civilization, but there were no noble savages here, just humans looking for resources. So when humans arrived to the south pacific and half the species of birds went extinct, he knew who to blame. There were birds over 6 feet tall in New Zealand, and even taller ones in Madagascar, that native peoples ate into oblivion. They must have been amazing to see. To quote the author, “as the mexican truck driver said who shot one of the last two imperial woodpeckers, largest of all the world’s woodpeckers, ‘It was a great piece of meat.'” A late poetic line I appreciated, “Every species makes its own farewell to the human partners who have served it so ill.”

The next section of the book was dire warnings of extinctions, which is simply out-of-date. And unfortunately, the conditions today are far worse than the time of the book’s publication. The author often refers to predictions for 2022, which has already come and past. If you want more up-to-date figures, the IUCN has reports on biological diversity. Personally I find it too depressing. I still do what I can regardless of reading the reports. Similarly, the many programs the author lists to create reserves or restore habitat are also often out-of-date. So much of the last third of the book was not particularly useful.

I will finish with a humorous moment I found. Edward O. Wilson, writing about a species, perhaps intending to be humorous, but not written so, “…dwarf members of a genus of giant salamanders.” So… regular-sized? It is good information he included, but the almost oxymoronic language gave me a chuckle. So read the book. It’s still a worthwhile read–even if you skip the end–by one of the premier naturalists of the last century.

Hoping to not lose all that I learned reading about ants for months, I wanted more. This book is part autobiography, part discovery, and part ant facts. With all due respect to Mr. Wilson’s autobiographical sections, my favorite parts were the latter two, especially the discovery. How did they discover one fact or another is often more fascinating than the facts themselves. For example, much of ant anatomy was discovered through histology, sectioning ants, and then reconstructing the insides.

Sometimes the experiments conducted can be a bit shocking. When studying the chemicals in the Dufour’s gland, Edward O. Wilson and his colleagues had to kill and harvest thousands of ants. Keeping in mind, however, that there are upwards of 200,000 ants per fire ant colony, it’s not more than a blip in the colony. Furthermore, no experiments have shown ants to have feelings and instead live only work to preserve the colony and create new ones, so it wasn’t cruel, but still somewhat gruesome. The real problem with this story is that it mentions a different scientist discovered that there are different chemicals to excite, to attract, and to lead the ants on a trail. But this book does not detail that experiment or where the other chemicals come from. The Ants may at times have been too thorough for a casual reader, this was often too sparse.

So in the end, I was somewhat disappointed with this book. Not because it was bad, but just lacked what I was looking for. It is an easy, casual read, and perhaps a decent introduction to further reading, but further reading is necessary.

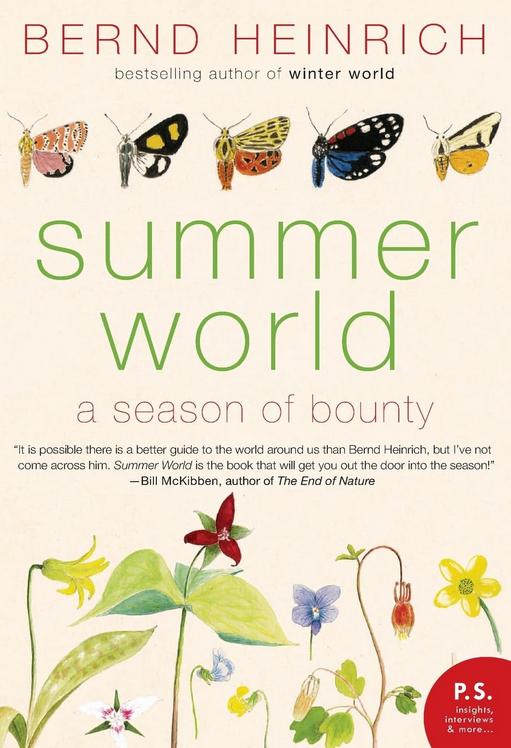

Summer World is yet another of Bernd Heinrich’s prodigious collection of works. Coming six years after Winter World, which I really enjoyed, Summer World is good, but not great. Part of the problem is the theme. For Winter World, everything always came back to freezing temperatures and surviving the freezing temperatures, often without food. But with Summer World, it’s just… everything. For instance, it’s as much spring as it is fall–or summer. The theme gets lost. The author attempts to fix this by inserting passages he wrote while at his cabin in Maine, using them as a thematic jumping off point. However, they aren’t in order, nor do they really add to the imparted ecological knowledge. To be fair to the author, part of my problem with this is that in these passages (and outside of them) he waxes poetic about the nature he sees on those dates, but this has never been the kind of writing I find interesting, and that is subjective. It contrasts with what I like so much about Heinrich’s writings, his experiments and studies of flora and fauna. He does write of these some in the book. Like how he analyzed water temperatures around frog eggs or observed ants moving colonies or making slave raids. As a side note, I appreciated the ant studies more, especially his correspondence with Bert Holldobler and Edward O. Wilson, since I read and reviewed their book The Ants just before this.

I also found the author was more preachy than normal, and on a few occasions spread through the book. I didn’t usually mind, since I am part of the choir (or perhaps the organist, since you wouldn’t want to hear me sing), but I think anyone reading the book is also part of the choir, so it wasn’t really necessary. On the other hand, were non-choir members reading Silent Spring? They must have been for it to have had such an impact, so maybe it’s a good thing. That said, there was some light religious preaching, which was odd. Perhaps I should define it as more spiritual.

Most of what I gained from this book wasn’t the author’s own studies or observations, but his explanation of what was happening based on other’s writings. Which is fine and not an indictment of the work. It’s actually pretty typical, and I enjoys his typical works. It just wasn’t my favorite Heinrich, Mind of the Raven. Each chapter typically covered some topic, like frogs breeding in vernal pools, mud dauber wasp nesting, or leaves falling at the end of the season, explaining them in sufficient detail and leaving questions when they were still unanswered by scientists. I learned a lot and enjoyed the experience, and I’m sure the author could write multiple sequels in the same format without remotely nearing the end of topics.

This is a mammoth of a book and not for the casual reader. It straddles the line of book and text book, so be warned. Another warning is that it was published in 1990, meaning entire careers of myrmecologists have come and gone in that span. I doubt a similar book could be written today, as it is so encompassingly thorough, that to expand it would be to break your desk. Any subsequent books would naturally have to be more condensed and summarized. It is so big and dense, that I probably would not have chosen to read it, except winning the Pulitzer Prize is a pretty big deal.

As a giant book, there is much to be said both good and bad. Sometimes there are no perfect solutions to a structural issue, as any path taken has problems, but I will start with some of my problems. One issue that was both good and bad is the discussion of theory. I think it is fantastic that so much evolutionary theory is taught in this book, but sometimes when a theory is explained, I spent a lot of effort learning it, and then the authors state that it is wrong. I would prefer them to state first that it is wrong, so I don’t try to commit it to memory as truth. And of the open questions theorized, but never resolved, I often wondered how many of the questions have been solved by modern genetic analysis. Again, the theory is important, so I was still happy to receive it. Most of the books I read present some information, but this one develops theory throughout. So if I read about new developments in myrmecology, the theoretical frameworks that I have now studied should help me contextualize, even if I have forgotten many of the details.

Another issue that cropped up from time to time is the method of organization that the two authors chose. When writing comprehensively, you can either explain each term or subject as it arises in the discourse of something else, or wait to develop them only when the appropriate category is elucidated. The authors here chose the later, which means I often googled terms or ant anatomy as I read. Though I do favor the former method, this isn’t really a criticism, it’s just their technique. If I was reading it as someone already at least moderately knowledgeable of ants, I’m sure it would have been fine. I wasn’t, but now I am.

There was, of course, much to enjoy, especially with how thorough the book is, filled with thousands of interesting aspects of ant life. My favorite topic was how much ant larvae are put to work. We have child labor laws, but ants don’t have play or love, they have work. Of the many tasks larvae have include feeding adult ants. Larvae may produce secretions, regurgitations, or even a snack out of their rear ends from digested food. Many larvae are even something of a snack. Queen ants often drink hemolymph, ant blood, from larvae. In some ant species, larvae are even physically adapted for this.

Aside from basically farming their own young, ants cultivate all sorts of crops and cattle. Some ants have other insects basically as cattle, sometimes using them as food, but mostly for what comes out of them–like honeydew out an aphid’s rear end, or a scale insect’s, or a caterpillar’s, or from a host of other insects. Even some trees are adapted to secret snacks (outside of their flowers) specifically to attract ants, which will then defend the tree from herbivorous insects and animals. Some ants even farm fungus. Fortunately, before reading this book, I had had the pleasure of seeing them do this at the Natural History Museum in NYC. Though the description in the book was more thorough.

The labor divide among female ants is interesting, as well as between the sexes. The lazy ant you find is likely a male ant, which lives for the purpose of inseminating a queen and then dying shortly after. But queens may live decades, while the longest-lived male ants get about a year, so we should cut the males some slack. There were cases of male larvae contributing, and maybe cases of adult males helping out have been discovered since this book came out.

Most importantly, this book has already been useful in understanding news stories. While writing this review, a study was published and widely publicized regarding how ant colonies in Africa impact an entire ecosystem, and how invasive ants consequently impact every trophic level. When explaining the article to friends, I was able to include more information because of my background, so I did really enjoy that. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/lions-are-changing-their-hunting-strategy-because-of-ant-invasion/

So in the end, I probably won’t continue to read text books, though I did get a lot more information from this one than even an equivalent number of pages from other books. It was, however, much more difficult to get through. From the fact that it never reads with ease, to trying to remember math for population genetics, to the sheer size of the book, it can be difficult. I am glad that someone at the library requested to check out this book while I had it in my possession, so it does still retain both relevance and readership, 34 years after publication.

It’s difficult to know what I would think of this book had I not just read Bernd Heinrich’s Mind of the Raven. One of the things I liked most about Heinrich’s book is that it lacked a lot of the fluff that many naturalist books have, which I had noted in Jennifer Ackerman’s other books, but found more prevalent this time around, perhaps, again, because I had just read Heinrich. That said, it was a good book. I learned a lot about owls from around the world. I appreciated that it was about just owls and not all birds, so learning was more thorough and retention was increased. I further enjoyed discovering more behind my own experiences. For example, a snowy owl I once saw in Delaware coincided with a year of abundance when the owls migrate far south.

I did not, however, find the book title apt. It was a book on owls, but not particularly focused on what they know, how they perceive, or what sensory world they exist in. All those topics were covered, but lightly. There was far more on owls in human culture than I would care to know. I understand that our knowledge is likely heavier on anecdotes than peer-reviewed studies of owl thought, but if the time isn’t ripe for a book with this title, than that is ok. We can wait.

I also found the attempts to push narrative aspects disjointed. That is, authors like to write themselves into non-fiction books to give them more personal touch, discussing people–and owls–they meet in the field. However, sometimes it’s just forced, and this was one of those times. So read the book to learn about owls and you will not be disappointed, but it’s not as in-depth as you may have originally expected.

Each time I read Bernd Heinrich, the experience improves–and I enjoyed the first book I read. I don’t know if that is that I have gotten used to his style or just luck that each one I read actually is better, Perhaps a bit of both. But either way, this is the best one so far. This is one of the longest, if not the longest, book I have reviewed, and it is the most exhaustive on a single subject, which is typically lacking in these books. Perhaps the only aspect missing in this book is detailed physiology, but the focus is on raven minds, more how they approach carcasses, less on how they digest them. And the way the author explains their minds–to the best of his ability–is through exhaustive and meticulous observation, which he shares at length (and to my reading pleasure).

I have commented in the past that Bernd Heinrich learns from experimentation. Most of this book is a (moderately) organized collection of observations he made studying ravens in the wild, wild ravens he caught and put into a large aviary, and ravens he hand-raised in his home and aviary. I cannot fathom the amount of time he spent watching those ravens from his window, from blinds, or from a distant vantage point, but I can appreciate it. I doubt that I would ever have the patience to do what he did.

I also appreciate how the author doesn’t curate his observations into clear and concise messages, skipping data that doesn’t fit, or emphasizing data to support his point. He details the many contradictions he observed in ravens. How they may fear some objects or situations, yet show zero fear if the circumstances or objects are only slightly different–or not even discernibly different to him. He also doesn’t jump to credit a raven’s ability to perform tasks to intelligence unless it’s been studied enough to actually rule out other explanations. His love for the birds is profound, but he works to study them dispassionately, even if he hand-reared the raven in question.

I think my favorite observation in the book was a potential co-evolution the author describes between raven and wolves where they both receive mutual benefits. Raven actually prefer to feed on carcasses with wolves present, finding it safer than without, but also lend wolves a much sharper alert system to any hidden dangers that may come along. Raven calls even seem to able to bring wolves to a corpse, which they cannot open up, but a wolf jaw can.

A quote I loved from the book, although not from the author, but from Craig Comstock, a Maine raven-watcher. “I understand the need for the scientific method, but… there are times when nature speaks just once, and it is a loss not to listen.” I think this quote is perfect for observing nature. We may not always prove any deeper meaning behind what we see, but it is always a worthwhile discovery.

The book details fascinating aspects of the evolution of brains, comparing very disparate species, and, if you couldn’t tell from the cover, focusing mostly on octopi and humans. And while social media loves to rehash the apparent cleverness of octopi and their cousins, it never really explains what that means, if it means anything at all. A philosopher and lover of octopi, cuttlefish, and squids, Peter Godfrey-Smith wants to discuss that issue with the reader. The author begins his his discussion with early evolution and the branches of animal life. He discusses studies and observations of our many-legged friends, comparing them to us. However, despite the clearly fascinating subject, I finished the book with a love-hate relationship. And to be clear, both “love” and “hate” are an overstatement. More of a like-dislike relationship with the book, though it doesn’t sound as good. The problems were two-fold. First of all, as a philosopher, Peter Godfrey-Smith seems to have a philosophy of asking questions, rather than attempting to find truths. This would be fine, except for that I did not feel his questions were well-defined or developed. Second, I thought that the actual science, the experiments and subsequent understanding of the octopus brain was lacking. I do not know how much he could have elaborated, but as he isn’t an expert, he likely didn’t know what questions he should be asking. After all, you don’t know what you don’t know. And without a strong background in neuroscience myself, all I knew was that I knew far too little to really examine any the question of what other minds might be like. It is a fine line, writing a book for mass readership, and writing a book with developed scientific discourse, but I did feel that this book fell short of expectation. It is well-written and interesting, but I would have liked another hundred pages of development before I felt like I even had a tiny grasp on the subject.

I think that the Nature of Oaks fixed the issues Tallamy had with his earlier work I reviewed. Bringing Nature Home felt too text-book for me. I understood what he was going for, but it was less-enjoyable of a read. This book stayed more narrative. Furthermore, I often lament that nature and ecology books are too broad. Learning about the intelligence of birds is great, but that is far too many species to track, so I greatly enjoyed that the main focus of this book was on a single genus of plants, and only in North America. That said, the fact that it focused on oaks did not limit Tallamy. While it examined oaks throughout the year, he used it as a jumping off point into interactions with and even between insects. Different seasons have different interactions. I might be inclined to say that the book was more simple than some of the others, but that might also be due to the fact that I have more background on the subject. But simple or not, I still learned plenty. My favorite bit of knowledge was learning of ant-caterpillar symbiosis. I knew of ants farming fungi, and ants caring for aphids, but not that some ants build little dens for certain co-evolved caterpillars to be safe, receiving secreted sugars in return. I recommend this book, especially for beginners, but also the more advanced.

This book by Candace Savage, reviewed earlier on her work writing about the Prairie, was not at all what I expected. It seems difficult for that to be the case, as the title is clear. The opening sentence of the book quickly demonstrates my problem. “Like most people, I have crow stories to tell. There was the time in the northern forest when a raven–and what is a raven except a crow taken to the extreme?–flew over my head….” I’m no expert on birding, but I think the only time in my experience that ravens and crows are confused as the same species are when I am the one confused, not from any author or scientific work I read. It is true that common names are somewhat meaningless and you really have to be careful and use scientific names when introducing a species so everyone knows which species is being discussed.

While reading the book, I learned that the author sort of focuses on the Corvus genus, with an emphasis on ravens, then crows, and then various other species. We don’t always know which kind of crow is being discussed, but she is pretty good at clarifying when it’s not properly called a crow, though you can’t always be sure–and there are situations you can’t be sure. As a work on the corvus genus, it was lacking, since it didn’t really talk about evolution or spread, so it wasn’t that kind of book.

This book was a combination of experiences people, mostly researchers, had with different members of the genus as well as stories, legends, myths, and artwork of different cultures. So there are aspects you wouldn’t get in a normal book, specifically the human cultural information, and some of the stories by researchers were new to me, but the choice in presentation was very strange. At least the book was very short, especially with all the photos.

Candace Savage has made a very long career being a non-fiction writer focusing on the natural world. She is not a professor or researcher of something specific, but has a broad background in her writing. I take that as a positive, because often I find that people highly involved in a subject are worse at explaining it because they are too technical and skip explaining principles that non-experts often need.

If it somehow wasn’t obvious, this book is about the prairie, specifically, the central North American grasslands. She begins many millions of years ago to explain the geology and how the ecosystem evolved to what it was at the beginning of European settlement and continues to its present problems. The book is very broad, because over the many thousands of square miles that constitute the prairie, there are a lot of interesting ecosystems, from playas to sandhills to short and tall grass prairies to name a few. She covered each one about as well as you can expect for a general book on the prairies, so it has made me realize how much more there is to learn, needing to get a book just on each ecosystem in order to feel like I actually understand them. But now I have a solid background.

This book was thorough and broad, and unfortunately, it read a lot like a text book. Many other authors I read have more of an angle. Bernd Heinrich explains many things, but often includes his own investigative science. Menno Schilthuizen and Olivia Judson use intriguing topics for their angles. Jennifer Ackerman works to write herself into each book to give them more of a narrative. This was just plain prairie writing. There was nothing bad about that, but it could be more difficult to concentrate. Actually it was more difficult to concentrate. Again, it wasn’t bad, it was technically very good, I just didn’t expect I would specifically miss authors who use an angle.

The only really odd thing was she refers to the Dirty Thirties a lot, but not the Dust Bowl. Having grown up where the Dust Bowl was, I never once heard of the Dirty Thirties It made me wonder about cultural differences in why someone would have a different name for it. Maybe it’s Canadian, or maybe it’s just from some book she read and she liked it.

So if you want a book background on the prairies of North America, read this book. You will learn a lot, but it will leave you wanting more, which is a good thing, because then you will read more.

The Homing Instinct is, in my admittedly limited experience, classic Bernd Heinrich. He interweaves his own studies and experiences, those of others, and an academic explanation of ecology to create this fascinating book. That said, much like in Winter World, it can sometimes be a little meandering for me. Ecology is complex, especially when it’s still cutting edge despite thousands of years of human study, and I often prefer a more rigorously rigid telling, with the facts lined up in a digestible order. That said, I understand the desire for a more loquacious method of explanation actually being more digestible for others.

Perhaps what I found most fascinating was to learn how much of a homing instinct is not an instinct, but is in fact learned knowledge. Like birds who want to fly north may have to learn a map of the stars. As someone who never learned where the big dipper is (so many groups of stars look like it to me), I’m even more impressed that they manage. In fact, a single bird may use a host of data points, including landmarks, the earth’s magnetic field, the sun, the stars, and the smells in the air. These small-brained animals can accomplish impressive feats of migration based on learned skills that we cannot always whitewash away with terms like “instinct.”

Another thing I liked about the book was the fact that while a bird is featured on the cover, and is what I typically read about when I do read about homing instincts, it was not the limit of this book. It really demonstrates how far the field can take us, how much more there is still to learn. Like my posts on structural coloration, every species is a window into a new realm with most yet to be studied thoroughly. Bernd only has so many pages in his book, but if you mentally take things a step further, you find yourself with more questions than when you started. In a good way.

The Homing Instinct is a worthwhile and enjoyable read. It may not be my favorite book, or even my favorite Bernd Heinrich, but I do recommend it.

This is the third of Jennifer Ackerman’s books that I have read, and while I will argue that it basically is a sequel to The Genius of Birds, I think it was also an improvement. It is called The Bird Way, but much of the book focused on understanding bird intelligence: How it is on display, where it comes from, and how it is used. However, Ackerman’s attempt to focus more on the birds’ way of life lent to a more in-depth understanding of different example species. Perhaps I simply do not remember The Genius of Birds as well as I would like, but I feel that that book flitted from species to species more often and rapidly than this one did.

Another reason that this book was more of a sequel to The Genius of Birds is that the author was careful not to repeat herself, using new birds and new behaviors to write about. Thus, if it was merely about the bird way of life, there would be more natural overlap, especially with the author’s own expertise, however she wisely stuck with new aspects of bird life and new species. There are some brief mentions of previously covered birds, but no real coverage, though having read the Genius of Birds, I understood these references better. Thus, I think this book was a sequel, but also superior.

One problem the book had was that Jennifer Ackerman does occasionally try too hard to play up bird intelligence. Bird intelligence is impressive and needs no help. However in the discussion on bird language, she liked to state that birds who understood alarm calls from another species knew another language. Birds understanding another species’ calls, not simply repeating them, is impressive. And those who repeat them for material gain are even more impressive. But a new language it is not. Besides, we can understand bird alarm calls and our ears can’t even pick out much of the details, but we don’t understand bird language.

Another issue with the book is its scope. One cannot cover all birds, but the author does seem to give it a go as she did in The Genius of Birds. I learned a lot of specifics, very interesting specifics that help me understand bird and animal evolution and a lot about ecology. Unfortunately for myself, learning about birds in Australia, New Zealand, and South America did less for me than learning about birds in North America. Of course, this is one of Ackerman’s main points, that ornithology has had an understandable northern hemisphere bias, so to correct that, she focuses elsewhere.

So read this book if you want to learn a lot about bird behavior, bird evolution, and bird intelligence. Do not read it if you want to learn about birds in North America or Europe, but if you do, you will still enjoy it.

This book took me a long time to read because I initially read twenty or so pages and then put it down for months. The meandering narrative in both the author’s thoughts and described actions are not typically what I like in a book about nature, though I know it’s a common trope. However, I eventually came back to to the book, curious about the topic and, having read more, came to the understanding that this is an intrinsic part of Bernd Heinrich’s process as a biologist. He is an experimenter who has to find and see and test. He describes tasting insects for the sweet antifreeze they produce, or heating up dead birds to measure the rate of heat loss in winter, or stuffing a roadkill chipmunk’s cheek pouch with seeds to see how many could fit. The meandering was not his laziness in writing, it was who he is as a biologist.

Winter World is, not surprisingly, a book about how animals (insects, rodents, squirrels, birds, etc.) survive the winter in freezing cold. It explains how they may build nests or huts, or how they can drop their body temperatures in torpor, or how they may even be effectively dead as they freeze solid, but then thaw and come back to life. The animal adaptations to winter are many, varied, and complex and this book does a great job explaining them.

It is also valuable that the book focuses on the northeastern United States, where the author lives. The reason this is beneficial is because often times authors take continent-wide or world-wide approaches to the natural world, but then the information about any particular area or habitat is diluted. I may not live in Maine, but I found this aspect to be advantageous to focusing my perspective and understanding the concepts.

It is worth noting that while the author starts out very meandering, he eventually moves into a much more traditional and categorical approach, suggesting he did not really have to go about it that way. But even in this later discussion, he still spends significant time talking about experimentation and observation, so he never loses himself

One other minor criticism was his declaration of what all entomologists believe theologically. And while he is certainly more qualified than I am to make such a statement as he is, in fact, an entomologist, talking for the entire group is still a bit too much.

So for starters, it should be noted that the original title of this book, “Notes from the Shore” was much more appropriate to this book in which very few birds make much of an appearance. It is more a book about the author and the shore around her home of Lewes, Delaware than anything else. I honestly would not have continued reading had it not been for the fantastic “Genius of Birds” reviewed earlier, as well as the fact that this was a short book. So while I held out for more bird information that did not come, I did not trap myself in a three hundred page read.

All that said, Birds by the Shore had a lot of interesting information about shoreline habitats, and the myriad of creatures who live there. There was information about various worms, crabs, fish, meiofauna, and yes, some about birds, which will be significant on virtually any trip to any shore. There was also information about the history of Lewes, Delaware and the human relationship with the land, making it a little more similar to The Pine Barrens reviewed earlier. Many nature/ecology books take a very broad approach, so it is important to also take time to read much more specific approaches to the field. Reading about birds across North America is great, but it can be too much information all together, so if you want a short read about the natural areas around Lewes, Delaware, you may want to give this one a shot.

Compared to most I have read, this book was plain and formatted in an unusually direct way, but I loved it for this simplicity. What it’s Like to be a Bird is a book on birds (no surprise), but with a lot of the normal dross removed, leaving only facts. Even favorite books of mine like Nature’s Nether Regions still contain a lot of information that add character, but I do not really find necessary, for instance personal anecdotes, that authorship and readers often require, but I generally do not. I love the science.

The odd formatting that I mentioned is likely due to the fact that David Allen Sibley is famous for his field guides, for instance, The Sibley Guide to Birds. The first section of this book is basically a series of facts in bullet points grouped into sections. Each fact directs the reader to the next section where the facts are lengthened into paragraphs. That section has each paragraph grouped into types of birds, e.g. terns, swallows, warblers, though sometimes individual species. The next section of the book is a paragraph about each species of bird mentioned, and the final sliver of a section is advice on what to do if you encounter a situation with birds, like a baby bird out of a nest (usually you should leave it alone).

In conclusion, for someone like me who is not very familiar with birds (I am more of a plant person), this book is very valuable to learn the breadth of behaviors, adaptations, shapes, and colors of birds across North America.

I said I wouldn’t give bad reviews of books, but that is because I assume everyone is writing in good faith, but I just don’t see it here. The author, Stefano Mancuso, might be an expert in plants… or maybe isn’t. I mean, his resume suggests he knows far more than I do, but it is not evident in this book. For starters, there is very little about plants in this book. For example, there was a section on coconuts, and I thought, “Great! I do not know nearly as much about coconuts as I would like.” Then, the author spent several pages relating a human-interest story about a sun-worshiping cult that believed eating coconuts would bring immortality. Yes, that is actually very interesting, but I also didn’t learn anything about coconuts, or what their incredible journey is.

I feel like Mancuso gave us a hint of actual ecology, but what he really wanted was a book like Michael Pollan’s Botany of Desire. Botany of Desire wasn’t heavy on the science, but it gave a lengthy description of the species it chose and the human relationship with each. That was clearly the goal of the book. This was very light on even that.

The reason I found the book so distasteful was its promotion–and actual bragging–about spreading invasive species. “True globalization. It has existed forever in nature. For plants, fortunately, tariffs, borders, travel bans, and barriers are meaningless concepts.” He’s not even technically correct. Clearly plants have found a litany of factors that prevented their invasive spread long before humans did the work for them. More shockingly is the fact that invasive species actually have many amazing features that make them invasive, but Mancuso fails to even relate that. I dislike invasives, but I can still respect the amazing adaptations that they have and can talk at length about many of them. This book won’t teach you that.

The author then took it a step further to actual state biological control of invasives was wrong-headed. “In the most fortunate cases they succeeded only in introducing a new species to worry about.” Biological control, when done improperly–as it has been at times in the past–has caused significant problems. And no, and biocontrol has not yet eradicated any invasive species (and probably will not), but it does help provide the ecosystem with some support for recovery. The fact that the author both promotes invasive species and denigrates biological control is without a doubt, a complete failure to understand ecology. Furthermore, if he really loves plants as he says he does, then he should be worried about the impending extinction of many rare plants pushed aside by invasives.

In conclusion, do not read this book. I was looking forward to both it and another by this author, but I will skip the second.

The Pine Barrens by journalist John McPhee is a book lost in time, and more beautiful because of it. The long-winded paragraphs match well with the long-winded nature of one of his favorite subjects, Fred Brown, a man as friendly as he is loquacious. While I do not normally prefer the style, it did the Pine Barrens justice in its narration, focused on how people lived and how communities began, evolved, and often died. I say that the book is lost in time because it evokes a sense of timelessness of the barrens that has since disappeared. The endless sand, pine, and oaks have often been replaced by pavement and housing developments. The stories of the strong, but elderly Fred Brown are no longer common.

The Pine Barrens is known as the barrens for a reason, it is a poor land, flat and sandy, but as the author notes, it is surprisingly rich in natural resources. The communities that grew often lived on the native materials such as the easily-accessible bog iron, the sand for glass-making, the blueberries, cranberries, huckleberries, the pine and holly for Christmas, the sphagnum, and the abundant wood. The Pine Barrens is perhaps, at first glance, uglier than other regions, but once a person gets to know it and gets to understand the rich interactions between the fire ecology, the sandy soils, and the plants, which include many types of orchids and native flowers, there is much to see and appreciate. Though the book focuses mostly on the humans of the barrens, it never strays far from the ecosystem that they depended upon.

One criticism of the book is that McPhee lauds the men and women who live in the barrens and demeans outsiders, especially city-dwellers. The people of the pines are upstanding, knowledgeable of the natural world, and forgiven of their ills, but those from New York or Philadelphia–or even just outside of the pines in New Jersey–are ignorant and greedy. As everyone knows, all groups contain good and bad types.

Near the end of the book, there is a quote that deserved more attention. Written in 1967, McPhee quotes one of his interviewees as saying ‘I will predict that if nothing at all is done in terms of planned development here, within twenty years the area will be so spotted with exploitative development that it will be impossible to assemble the land into something that is sensibly planned. The state has about five years in which to act.” While the man was promoting the development of a planned city that would concentrate people and protect the environment out side of the area, he was correct. Today there remain some very large protected tracts of land, but it is still far, far more developed than it was when the book was written. Highways lined with houses crisscross the pines, breaking up the habitats into fragments, favoring vacationers, commuters, and those who simply wanted to live somewhere more affordable, over the wildlife that had so dominated.

It is a good read, and I recommend it, but it’s not ecologically focused, so one should take that into consideration if wanting specifically to understand the unique ecology in depth.

If you like a clever oomph to a book to keep it fresh, this might be the book for you. In essence, it is a book about evolution and sex, but with the shtick that it is written like a sex-advice column where various creatures ask Dr. Tatiana questions about what they are going through. The character then responds, explaining not only that issue, but similar traits throughout the spectrum of life on Earth. It is a fun and easy read and people who give it a shot will likely enjoy it.

I wonder how I would think about this book had I not already read Nature’s Nether Regions (reviewed below), which I found to be superior in most ways. For starters, the topic did not really need an embellishing shtick, and many times the author tried too hard, using overly-vulgar terms that one probably wouldn’t find in an advice column. I also found the structure of Nature’s Nether Regions to be better, though the further I got through Dr. Tatiana, the more I appreciated the format. I think it also simply got better as it went.

I wanted to read this book in part because I really wanted to reread Nature’s Nether Regions. It had so much information that it was difficult to retain it all, but it’s hard to reread a book when there are so many more to get to. This one covered many of the topics Menno Schilthuizen did, but also had significant variation, so it was not just review, but contained totally new information. Thus, there is also no reason for concern about reading both.

How Plants Work by Linda Chalker-Scott was a deviation from my normal type of reading. For starters, it read more like a text book than the others (similar to the second half of Tallamy’s Bringing Nature Home). Secondly, it was oriented towards the gardener, not the ecologist. However, neither one of these changes was a problem for this quick and informative read. While the text-book like atmosphere may sound dull, it was not, and sometimes it takes lengthy explanations to convey complex science, which was the main point of the book and the main reason I read it. Aspects of plant physiology sometimes get left behind in explanations of ecosystems. Some books will explain what the behavior is, but not how it comes to be. Thus, I like to read the chemistry behind the actions and the author accomplished that well.

Regarding the fact that the book was tailored for gardeners was something I was skeptical of, but found appreciation in because restoration ecology often involves many aspects Dr. Chalker-Scott covered in the book. Whether testing soil for a variety of nutrients or to root behavior in different seasons, there is much to learn before attempting ecological restoration. One of my favorite facts was learning about arsenic used as an orchard pesticide in the early-mid 20th century, which can still cause toxic conditions today.

There was one minor problem with the book and that was when the author brushed off the importance of native species and actually recommended planting non-invasive non-natives. One tree (Japanese maple) that she loves to write about in her yard is actually a new invasive, demonstrating that just because something has not yet become invasive does not mean it won’t. She also claims the biodiversity created by the extra non-natives will help the ecosystem, but that is factually incorrect. The non-natives support far fewer insects and animals than the natives do. So I found this one half-page comment frustrating, but over all, the book was very informative while managing to be an easy read, which is a challenging task.

This book was a difficult one to review because there was much to love about it, but also much to be disappointed by. In this book, Menno Schilthuizen does a wonderful job going over the many facets of how plants and animals deal with human impacts, whether they evolve to our pollution, be it chemical, light, or noise, if they adapt to survive death traps like cars, or if they simply do a better job blending into the changing surroundings. He delves further into how they evolve, including small changes to their physical sizes, alterations of chromosomes, new coloration, and novel behavioral patterns (genetic or learned).

At the same time, Menno does not acknowledge what invasive species really do to our urban and rural ecosystems. It is a topic completely ignored. A single invasive species can, and has, made several native species go extinct while providing little. He also states that invasives are often best-suited to adapting to urban-living, but ignores why this is so-that they merely benefit from a lack of predation and typically provide little benefit to the urban ecosystem. If he wants cities to be the purview of a very select few species, then invasives will do quite nicely. For the ecosystems to adapt to those invasives, however, when they become full contributors to the food web, they will need thousands of years to fully integrate them. Thus, while embracing invasives may seem like a chic embrace of the future, it is a really bleak omen for most species. In conclusion, the book is wonderful at explaining what is happening, but is highly problematic at its promotion of the McDonaldization of the world’s ecosystems.

I really enjoyed reading The Genius of Birds by Jennifer Ackerman and highly recommend reading it. It was packed full of studies on birds and their intelligence, whether it was building tools, migrating long distances, or solving human-designed puzzles. There are a lot of ways to think about intelligence and what it means. As anyone who has raised children knows, things that may seem mundane from a surface observation can actually be significant and show significant thought and understanding. Furthermore, while the book was detailed and full of science, it was well-written, not bogging the reader down like a college text book might.

One thing I especially appreciated was the fact that the studies were cited, so anyone can read more in-depth on each one, clarifying a point, learning more, or checking up on the book’s author. Honestly, there was far more than I ever would have expected, which is a great thing when you want to consume a lot of knowledge. She did call Afghanistan part of the Middle East, but I’ll let that slide. Read this to learn about birds, about animal intelligence, or just to have fun reading.

Bringing Nature Home was written by entymologist Douglas Tallamy, and though the book has much about insects, it is not a book about insects. It is a book about ecology. Tallamy’s work with insects has lead him to become something of a native plant guru, because plants, and the insects who feed on them, and the insects/animals who feed on those insects (and so on), are completely interlinked. Thus, he thoroughly explains the problems with invasive plant species and the threats they pose to our entire ecosystem. Fortunately, he also explains what the reader can do to help (hint: plant native plants in your garden).

The second part of the book is a little less interesting in showing relationships within an ecosystem, but great if you want pictures and explanations of specific plants and insects. I read it all, but it is a little dry. That said, one of my favorites were the tortoise beetles that carry their own feces like a an umbrella above their heads. If you were a bird, would you want to eat that?

Nature’s Nether Regions by Menno Schilthuizen was absolutely fantastic. Yes it is about genitalia and the myriad of jokes that come with them, but it is also about evolution, specifically the competition between males and females and even between hermaphrodites that are both male and female. Genitals evolved across animals in such a diverse manner that they are literally the cornerstone for much of insect species identification. From monkeys with spikes on their genitals to male bedbugs who inseminate females via other males to land snails who shoot love darts at each other, the variation seems endless. I suspect the author had to hold himself back from writing the book twice as long as the published form, there was so much to say.

My favorite quote: “The penises of beetles, flies, butterflies, moths, and many other insects often carry such accessories (although they are called by different names in different types of insects), and they are used to drum, tap, slap, or stroke the outside of a female’s genital region during sex while the rest of the aedaegus is working on her inside.”

The Botany of Desire by Michael Pollan was a very interesting book about the historical relationship between humans and some of our crops, specifically apples, potatoes, marijuana, and tulips. I was hugely disappointed that he refused to eat GMO potatoes without really being able to explain why, especially considering his talk of potatoes made me feel the GMO ones were cleaner (fewer pesticides). But it was well-written and thought-provoking in general. We often think about our crops as our crops, but not a relationship going back thousands of years.