During our pandemic-derived societal quarantine, many of us have felt heightened depression, isolated from gatherings that we normally love. Maybe we see less of our family, maybe we date while wearing face-masks, maybe we can’t attend sporting games, and so on. We may ask ourselves, “What actions of ours brought us here?” and then look at policy changes as well as behavioral changes so that we do not reach this point again. However, we may also look at how we have forced a similar situation on so much of Earth’s wildlife. Through development and farming, we have left behind slivers of habitat, isolating much of the wildlife inside from fragments elsewhere. This is known as habitat fragmentation.

Some wildlife is effected less by fragmentation, often because it can fly like birds and many insects, or it can walk through human areas with relative ease like deer and coyotes. Unfortunately, many plants and animals have difficulty and end up permanently stranded. Thus, populations within one park may be completely isolated from the rest of its species. Furthermore, while we often imagine that cities are pockets of human areas inside vast wild areas–both of which are very distinct–this convenient thought is not true. We ignore the sprawl of modern suburban developments and many-lane highways which blanket or crisscross what we imagine to be “wild.” In much of the world, it is more appropriate to consider wild areas to be small areas surrounded by human ones.

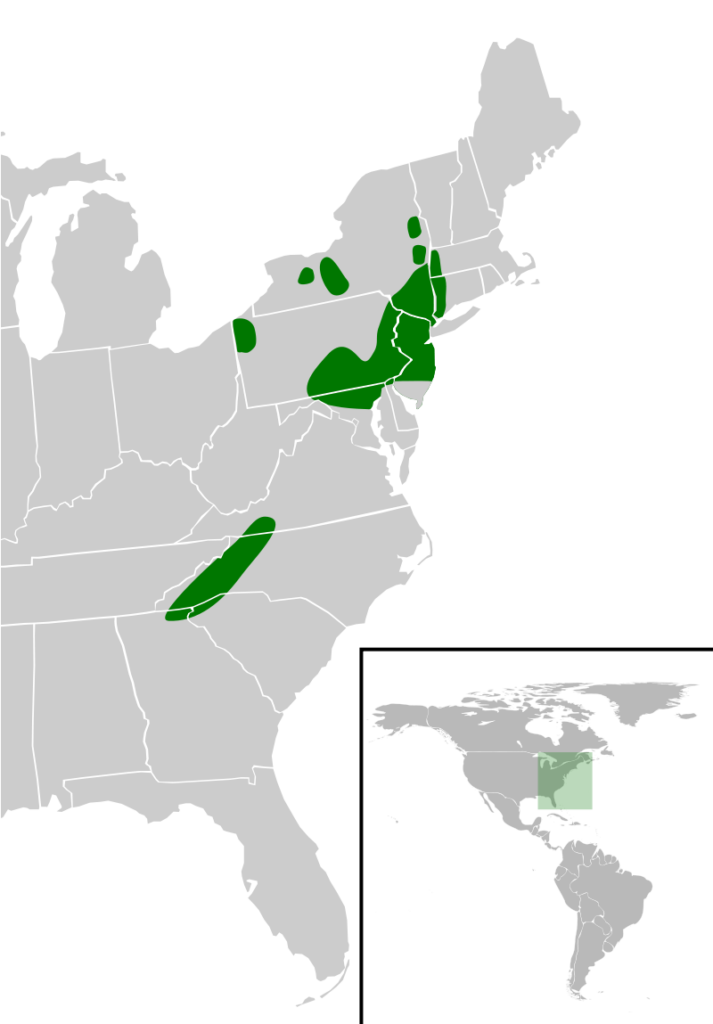

Source: By US Army Corps of Engineers – http://www.sas.usace.army.mil/rbogtrtl.htm

One tragic example that highlights the problem of habitat fragmentation is the bog turtle. Bog turtles are small, slow moving, and easy prey. As the name implies, they often live in bogs as well as other wetlands in the eastern United States. Unfortunately, humans have done a fantastic job at draining many wetlands and cordoning off others. Thus, if a bog turtle wishes to venture out from his or her own wetland to socialize with more of its species, it often needs to cross relatively large developed areas of lawn, road, highway, lots, or other “improved” structures. Now, while even a slow-moving creature can make it from one place to another–and even get lucky crossing a road–so some populations can interbred, others are too isolated to branch out. In fact, the species is typically separated into distinct northern and southern populations because there is simply too much development in the Shenandoah Valley and they cannot make it across. The populations are genetically distinct and will, over time, diverge into separate species.

Bog turtles are certainly not the only example one could use, but the image of a turtle trying to cross developed areas is easy to understand. But bobcats, snakes, many insects, and even wild mice can be affected by fragmentation. This brings us to some important aspects of habitat fragmentation’s damage. Not only is it lonelier for social creatures, and not only are their genetic pools less diverse and suspect to disease, but a small population can drop below a critical number and then crash. As an obvious example, even a reproductively prodigious animal like rabbits cannot overcome a population collapse down to a single individual. Some species require very few, but others need many individuals.

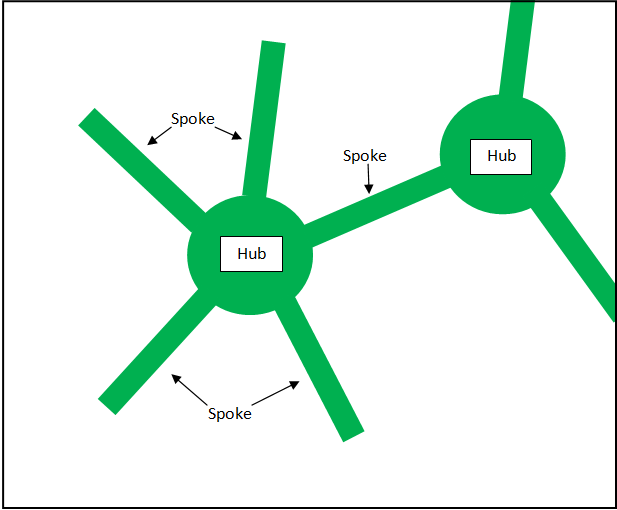

Fortunately, there are efforts to improve connectivity of habitat fragmentation through the hub and spoke technique, where parks and wildlife areas are hubs, connected by narrow—often riparian—corridors. By protecting riparian buffers along streams and rivers, we create avenues for wildlife to travel longer distances through human-developed regions. This helps keep populations of wildlife interconnected, mingling, and stronger in their genetic diversity. Certainly larger contiguous areas set aside for wildlife are better, but in absence of those, the hub and spoke technique is a significant improvement.